Trout: new markets, new technology

Hofseth is one of Norway’s biggest salmon processors, handling more than 50,000 tonnes each year, but it is also a producer of farmed salmon and trout, totalling around 16,000 tonnes with 70% accounted for by trout.

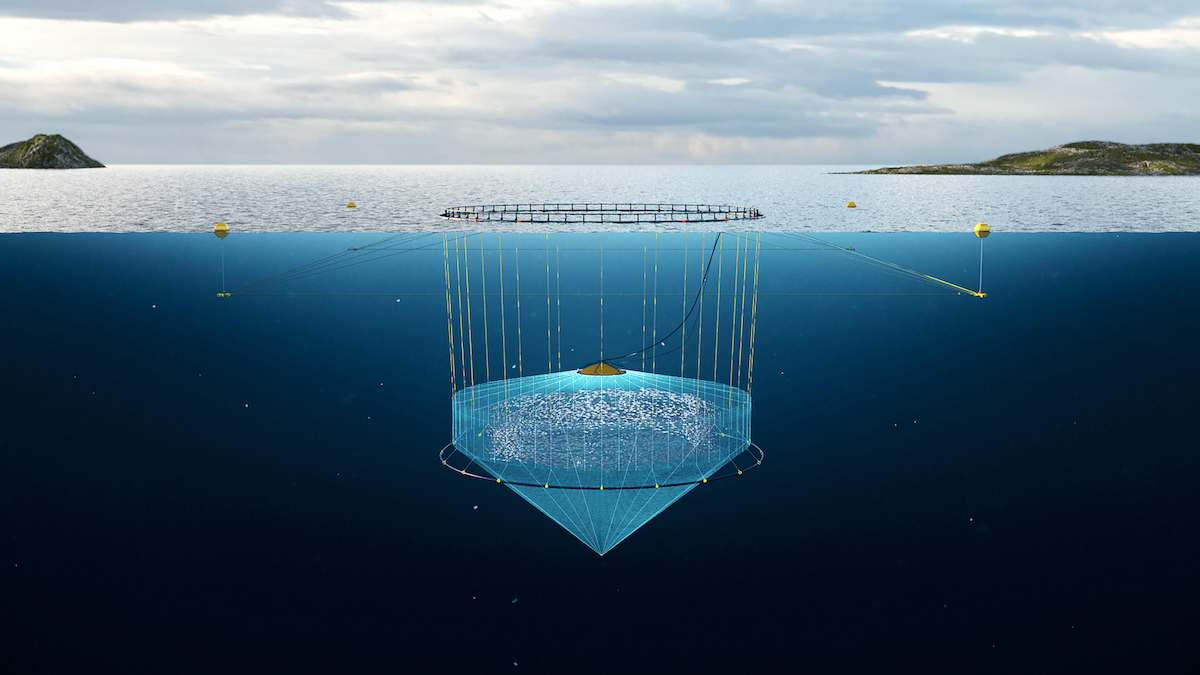

In March, Hofseth reached a major milestone by releasing the first trout into a submersible cage at Bugane in Storfjorden. This marks the beginning of a new chapter in sustainable aquaculture, as the company becomes the first in Norway to test this technology specifically on trout.

There are nine submersible cages at Bugane, six with trout and three holding salmon.

Bugane is located in Storfjorden, a 110-km long fjord in Møre og Romsdal county It is a large fjord with five fish farming sites, all operated by Hofseth.

As Didrik Vartdal, Quality Manager at Hofseth Aqua, explains: “We invested in submersible farming at the location we saw as most exposed to acquiring and spreading sea lice, making it a good test area for the new cages.”

Hofseth has been working with Norway’s Institute of Marine Research (IMR), which has carried out smaller scale tests of submersible cages with sea trout.

Vartdal says: “One of our goals is to increase production without increasing the lice population.

“The more sites you have, the higher the transmission intensity for sea lice, so taking out two or three sites can significantly reduce lice transmission.”

It is part of a programme to achieve better fish welfare using delousing methods that are specifically adapted to each fish group. This can include freshwater treatments or combination treatments that are less harmful to the fish.

Another measure is to rear salmon and trout smolts for a longer period on land before releasing them into sea cages.

The new cages are suspended at a depth of 20 metres from the surface, below the five-metre layer of ocean in which most sea lice can be found. Each cage holds 40,000 cubic metres and can take up to 180,000 individual fish at 5kg.

An air dome in the cage provides access to air for the trout’s swim bladders, which the fish need for buoyancy.

To get pellets to the fish that far below the surface, waterborne feeding is used, governed by camera surveillance which makes use of machine learning to monitor not only feeding behaviour but also the condition of the fish. Waterborne feeding is also more energy efficient, and quieter, Vartdal says.

The cages were developed by AKVA and the camera system comes from Aquabyte, but other suppliers are also competing in this field.

Not all locations are suitable for submersible cages. The best are exposed locations with a high rate of water exchange, and therefore rich in dissolved oxygen. The cages also require relatively deep water, with a minimum of around 200 metres, but they also need to be close enough to shore for the necessary infrastructure and access to power.

Norway’s coastal geography has plenty of such locations, but that is not true of all fish farming regions.

Fouling at such depths is less severe than for cages nearer the surface, but the nets are impregnated with a biocide and can be cleaned with a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) if needed.

Vartdal says: “The trout have adapted well – faster than the salmon have.”

So far, signs are that lice treatments have not been needed, the feed conversion ratio (FCR) has been good and mortalities are down.

The first harvest from the submersible cages is expected towards the end of this year, when the fish should have reached between four and four and half kilos.

Meanwhile Norway’s “traffic light” system, which regulates fish farming by region depending on the perceived sea lice risk, does not make allowances for submersible cages as a special case, but as Vartdal points out, actually reducing sea lice transmission could help to turn a “red” zone “green”.

Finnforel branches out

In a field where the product can often be seen as a commodity, Finnish trout farmer Finnforel is looking to differentiate not only its fish but its whole production process, based on what the company calls the “gigafactory” concept.

Finnforel farms its trout in a land-based, recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) facility which prioritises quality and a low environmental impact. CEO Nora Hortling, who took up her post in February this year, explains that Finnforel controls the entire value chain, from breeding to processing and packaging.

This includes having the company’s own breeding facility and a programme with the National Resource Institute of Finland to develop a breed even more suitable for a RAS environment. She highlights convenience as a key differentiator for the product, noting that Finnforel’s fish fillets are portioned for single servings, reducing food waste and making meal preparation easy for consumers.

How does the operation compare with farming trout at sea? While the initial capital expenditure for a RAS farm is significant, the environment means costs are more predictable, Hortling argues, unlike open net farming.

She says: “We have a quite stable environment. Of course it needs a lot of expertise and experience to run that environment in a sustainable way, but I’d say it is very competitive. As the industry evolves and learns, it will constantly also get more efficient.”

Finnforel’s newer plant, completed last year and based alongside the company’s first RAS farm, utilises raceways that are shallower and more energy-efficient than the traditional deep, round tanks in the older farm, leading to better environmental control and energy savings.

Finnforel’s home market is Finland, but its primary current focus for export is the Middle East. Last month, the company announced that its LoHi export brand trout is now available in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The products have already made their debut with the start of sales in selected LuLu Hypermarket stores in Dubai, one of the UAE’s largest retail chains.

Additional retail partnerships with two other major local supermarket chains in the UAE are set to begin in the coming months.

Nora Hortling confirms that Finnforel is systematically exploring new export markets in Europe, Asia and the US, although she notes that these discussions require significant time and effort for a relatively small brand from Finland (the site’s full capacity is around 2,800 tonnes).

Hortling also shares the company’s vision to expand the “gigafactory concept” globally to be closer to consumers, with several potential international locations already identified and initial plans underway.

She says: “We need to scale our sales to match production. So, that’s where our focus right now is. But of course, in the background, we are constantly also working on our future expansion plans internationally.”

Finnforel has already collaborated with the UAE-based investment organisation ADQ on the schematic design for a plant in the UAE. The two partners mutually decided to delay further decisions on this project, however, which remains active but not currently in full development. Meanwhile Finnforel intends to observe market reception to its brand in the region.

UK trout farming: the times they are a-changing

In the UK, the scale and nature of trout farming contrasts starkly with the huge salmon sector – but trout farmers are having a good year, says the industry’s association.

Oliver Robinson, Chair of the British Trout Association (BTA), reported that the demand for trout is strong, but the industry has seen significant changes and a reduction in UK production. Notably, in 2023 Dawnfresh, which operated trout farms in the west of Scotland, was acquired by Mowi, which converted two sites to salmon smolt production. This has resulted in a loss of approximately 5,000 tons of trout production.

The remaining Dawnfresh sites were sold to Gael Force’s subsidiary SeaQure Farming in April of this year, which is enthusiastic about developing trout production, particularly at the Ardnish site which will operate a semi-closed containment system. Some of the Dawnfresh staff were retained by Gael Force, preserving valuable industry experience.

Meanwhile in England, the Trafalgar Fisheries rainbow trout farm near Salisbury closed in March this year and another company, Coldwater Salmon Ltd, is seeking planning permission to convert the site to a land-based salmon farm. Its proposal to cover the open farm site with a 3,240 square metre steel and PVC canopy could prove controversial.

Oliver Robinson estimates that UK trout production for the table is now around 12,000-13,000 tonnes, from 17,000 tonnes prior to the Dawnfresh takeover. Included in this is 3,000 tonnes, estimated, for restocking in rivers and lakes.

He has observed a significant industry trend over the past few years toward producing large freshwater trout, often three kilogram-plus fish, through flow-through systems, rather than the smaller portion trout that used to be a feature of the market, noting a very strong demand for this product. These larger trout tend to be processed either as fillets, G&G (gilled and gutted) or as hot or cold smoked trout.

Finally, while many hatcheries in the fry or fingerling sector have closed over the years, Robinson says, those that remain have full order books, indicating continued demand.

It has been a warm summer, which can typically be challenging for fish welfare, but the BTA has so far seen 2025 as a good year for the trout farmers. Robinson says: “Health and welfare has been quite an interesting battle for people this year, because of the summer we’ve had, but generally, because we had such a wet winter, there were very good flows in the rivers in the early summer.

“Antibiotic use is down again down to the realms of about four to five mg per kilo produced, which is quite good.”

Proliferative kidney disease (PKD) has been a challenge across the UK and globally. A significant grant from the Sustainable Aquaculture Innovation Centre (SAIC) is funding research into PKD with Aberdeen and Nottingham Universities, which are working with leading Scottish trout farmer Kames. Meanwhile, a worldwide PKD group has been established with the hope of driving understanding and solutions.

Robinson is excited about the potential for a PKD vaccine, with a group in Vienna possibly conducting lab trials next year, for example. Currently, farms rely on a natural immunity process, in which fish are exposed to PKD in July to develop immunity for the following year.

Robinson emphasises the vital need for continued funding for SAIC, particularly for the trout industry, which is generally the preserve of independent companies rather than well-financed multi-nationals.

Trout welfare hit the news this summer when campaign group Animal Equality released video footage of fish at Bibury Trout Farm being despatched in an inhumane manner. Bibury, in the Cotswolds, raises fish to be caught by paying visitors. The fish are killed – as is regular practice in angling – with a “priest” or baton, and it was members of the public rather than staff who appeared to be disregarding the instructions given to visitors on humane slaughter.

Just as for salmon, fish welfare is an increasingly public issue and the UK trout sector has been working for three years with Lord Trees – a qualified veterinary practitioner as well as a member of the House of Lords – on health and welfare at the time of slaughter for trout, with recommendations now awaiting ministerial decision for the UK.

Efforts are underway to develop an affordable and usable batch stunning solution, potentially electrical, for smaller farms, in collaboration with Ace Aquatech, with a long-term goal of rolling this out across the entire trout sector.

Meanwhile, another concern for Oliver Robinson is a potential change in the law on licensing water extraction. Environmental legislation currently underway for England and Wales, known as environmental protection regulation, would swap a “licence of right” (effectively a permanent licence) for a “permit” under which, it seems, the Environment Agency could change abstraction volumes if it was felt a greater need presented itself.

Robinson says that the Environment Agency has assured the industry that permits will not be time-limited, and that if they are changed then compensation will be payable. These details could be changed by a future government, however, and the BTA is calling on government to provide stronger guarantees in the legislation, so as not to deter investment in aquaculture.

Kames: a year of accolades

It’s been quite a year for Kames Fish Farming, which farms trout on the west coast of Scotland. Stuart Cannon, now Chairman of the company, was awarded the MBE in the New Year honours list, and in June he was given the Outstanding Contribution award, as voted on by the aquaculture sector at the 2025 Aquaculture Awards in Inverness.

The company also picked up an award for Innovation, and Fish Health Manager Andre Van was named as Emerging Talent of the Year, at the M&S Select Farm awards.

Meanwhile, in February the company rolled out its new brand, MòR Atlantic Trout. “MòR” is Scots Gaelic for “big” or “great”.

The brand aims to emphasis the size and superior nature of the steelhead trout from Kames’ own broodstock programme, while stressing “Atlantic” identifies the fish as raised in the sea, with the clean water and strong currents of the Inner Hebrides – differentiating the product from river-based trout which can be associated with a muddy flavour.

Stuart’s son Andrew, Kames’ Managing Director, says the key focus of the MòR brand was the US market. While Kames’ steelhead trout already has a reputation in the UK, especially in the hotel and restaurant sector, it was less well known in the States.

He says: “We wanted to put our mark on the industry and it’s been great. It’s really helped us to get nearer to the chefs and to the end consumer.”

Cannon adds that 2025 production has been good so far, despite initial concerns about the warm spring and early summer sea temperatures. He notes: “It held back some of our production a little bit, because you have to treat the fish a little bit more gently and you don’t feed them as hard.”

He explains that Kames’ broodstock programme, working with genetic specialists Xelect, helps them manage challenges like jellyfish activity and helps the fish to adapt to warmer sea temperatures, making their strain more resilient.

Cannon says: “We’re continually breeding from the ones who are the strongest survivors.

“We believe in saltwater farming. We think that gives you the purest, cleanest taste for the trout, but also gives you that texture and colour you want. They are the three things that we’re after.”

In fact, this year the freshwater stage has been one of the most challenging parts of the business. As other trout farmers have found, PKD is a concern and Kames is working with the universities of Nottingham and Aberdeen to help find solutions for the industry.

Trout is also subject to the same price pressures as salmon, and Cannon has seen the latest uptick in the market with some relief.

Expansion for fish farming along the Scottish coast is not easy, but Kames holds out hopes that some existing salmon farm sites might prove more suitable for a trout farmer.

Cannon says: “There are some sites that don’t suit the salmon farmers very well, maybe in slightly more brackish water and slightly smaller sites. The 1,000 to 1,500 tonne sites suit us down to the ground as more artisanal trout farmers.

“They [the salmon farmers] don’t want to be going along to a 70 metre cage and taking out salmon from there. It’s not a big enough infrastructure for them, but it’s perfect for us.”

Meanwhile, Cannon is very proud of his dedicated team.

As he puts it: “We probably have to work harder than the salmon farms because I’m asking people to do a little bit of everything rather than a lot of one thing. But I think that we’ve got fantastic personalities who like that. They really know how valuable they are to us, and they really believe in trout.”

Why not try these links to see what our Fish Farmer AI can tell you.

(Please note this is an experimental service)