Northern star on the rise?

For a country with such a strong seafood tradition, Iceland was rather slow in getting into aquaculture.

A decade or so ago, the sector barely existed, with an output of less than 3,000 tons a year. But by 2024 the country was producing 55,000 tons, mostly Atlantic salmon, with Arctic char in second place.

The 2025 figures have yet to be published, but lice infestation problems in the Westfjords may have led to a temporary reduction, with volcanic eruptions leading to a decline in Arctic char output.

Nevertheless, with several new, mostly land-based, projects in various stages of progress, the overall strategic path has to be upwards.

Iceland is strategically well placed for the lucrative US market, despite tariffs. It is also making steady inroads into Europe and the Far East.

Within the next decade the country may well be one of the top five Atlantic salmon producers, taking over from the Faroe Islands, although speculation that it could push Scotland out of third place are probably wide of the mark for some years yet.

The Icelandic government, having produced a major report on the future of fish farming last year, has already signalled the direction it wants the industry to take.

Just before Christmas, the Reykjavik government announced broad details of a new comprehensive law on aquaculture, in which many of the changes stem from a National Audit Office report from two years ago, which was critical of the industry, saying its administration was too weak and too fragmented.

Many of the proposed changes stem from this report.

The Minister of Industry and Trade, Hanna Katrín Friðriksson, wants to strengthen the legal framework for aquaculture and combat its negative environmental impacts with new comprehensive legislation.

The aim, she says, is to create a more solid foundation for sustainable value creation in aquaculture.

Among the main changes regarding sea pen farming are increased incentives for the use of closed equipment and infertile salmon, more effective responses to discharges, and stricter rules for monitoring the sexual maturity of farmed salmon.

There is also provision for increased control and response to lice infestations, and risk-managed planning with the introduction of infection control zones. Minister Friðriksson also proposes that the Fisheries Fund be abolished as part of administrative simplification, and that fees be based on the industry’s performance to ensure competitiveness.

The bill specifically addresses land-based aquaculture in a separate chapter, in which regulations would be adapted to specific situations, including in terms of licensing, supervision, infection control, and animal health.

The report points out that current laws have largely been formulated with the needs of sea aquaculture in mind and do not adequately address the challenges associated with land-based aquaculture.

Sea-based aquaculture is discussed in a separate section of the bill, but this branch of the industry is still at the concept stage in Iceland, so immediate action can wait.

Finally, the bill discusses fjord farming, which is a new and undeveloped branch of aquaculture.

This system involves keeping fish in a closed cage at depth and feeding exclusively on natural zooplankton that is attracted to the cage using optical technology.

The intention is to provide legal support for such experiments and later assess whether there will be grounds for the establishment of more detailed rules.

The Ministry is now inviting comments, observations and suggestion on its plan.

While there are soothing noises from ministers, experience in other countries, notably Norway and Canada, show that when governments become involved, the industry is none too pleased.

Relations between the government and the deep sea fishing industry over a cut in mackerel catches have deteriorated in recent months.

The Norwegian experience is a classic example of how the salmon industry and government can end up with daggers drawn, especially when it comes to tax.

And there is opposition to the plans from conservation groups. The Wild Salmon Conservation Fund, which wants to ban sea cage farming altogether, has said the draft bill on aquaculture “does not meet the demands of voters”.

The organisation claims that sea cage farming causes environmental damage in every country where it takes place and wants it banned in Iceland.

There is strong support for the fund’s cause away from fish farming areas, especially in the capital Reykjavik. So the government may face strong political pressure.

The two main Icelandic salmon producing regions are the Westfjords and the Eastfjords, where aquaculture expansion has been reviving the economic fortunes of these areas.

The fishing and aquaculture employer organisation SFS says that aquaculture has increased the number of sources of foreign exchange for the national economy and has accounted for more than 5% of the value of all merchandise exports.

It adds: “This development is extremely positive, as strong and diverse exports are a fundamental prerequisite for improved living standards in this country.

Aquaculture already has a major economic impact on the people of the various regions, and its impact is not lost on those who live there.

“The economy has become more dynamic and diverse, the population has increased, and more life has entered the real estate market, to name a few.

“This can be attributed directly to the increased activity of the aquaculture companies themselves, and indirectly to the spill-over effects that the activities have on other industries.”

The Menon report, produced for SFS, the Icelandic seafood employer organisation, says: “The economic value of aquaculture is likely to grow even further beyond the next decade as the sectors included in the analysis reach maturity.

“Achieving maturity typically grows a sector’s tax footprint, as operations become profitable and corporate tax income grows.

“However, if not managed carefully, industry growth can also have less desired impacts, primarily on the environment. All in all, a growth of this scale will have wide ranging impact on Icelandic society.”

SFS adds: “Iceland’s aquaculture strategy and resulting policy should seek to amplify positive impacts while limiting negative impacts. This involves prioritising and making trade-offs that may also impact other industries.

“Done right, this will result in a balance where economic value is captured through sustainable industry growth that occurs in harmony with the environment and society.”

The report also says that overall, Iceland is an attractive location for traditional farming due to its naturally suitable conditions and availability of capacity in fjords.

“Further growth would be supported by increasing the overall maturity of the supply chain and strengthening the regulatory system. Iceland is still expected to double production from traditional farming within the limits of current regulations.

“This in contrast to the other major salmon farming countries, where future growth from traditional farming is constrained by natural capacity and must be driven primarily by efficiency-enhancing technology.

“Iceland has experienced rapid growth in production, fuelled by private investment, since 2016, demonstrating its attractiveness as a site for traditional salmon farming.”

However, the existing methods used for traditional farming in Iceland face key environmental challenges, and are unlikely to propel the salmon industry much beyond twice its current economic size.

As with Norway, salmon farming is divided into traditional (fjord based) and land based. Traditional operations have increased at a 35% compound annual growth rate over the past decade.

Iceland’s fjords, like those of Norway and Scotland, are well suited for this type of aquaculture and have the potential to grow up to 100,000 tons, says the report. And, for the most part, disease is less prevalent.

There are challenges, however, from sea lice, and research is not as advanced as in other countries.

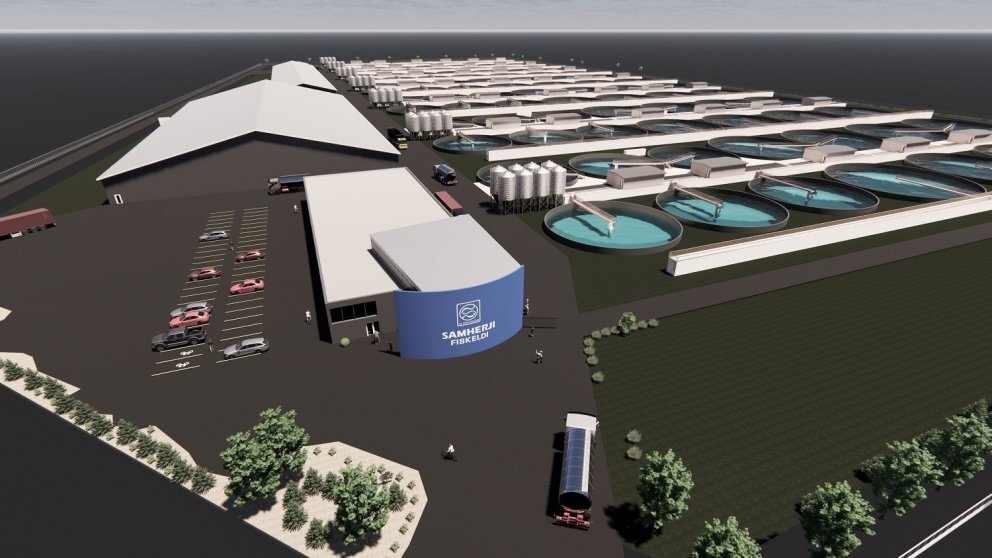

Ongoing projects in Iceland have plans to deliver up to 125,000 tons of output across four companies, but most of these projects are in their early stages.

There is talk of Iceland developing offshore salmon farming, but it is still just talk. In Norway, where developments are more advanced, this sector has yet to properly get off the ground.

Iceland may want to wait and see how the Norwegians progress before venturing themselves. I would suspect that offshore farming in Iceland is at least a decade away. Overall, Iceland is in a good place when it comes to the development of its aquaculture industry, provided the government doesn’t interfere too much.

Improvements to the country’s transport infrastructure are badly needed and that is an area where government can, and should, interfere.

Economic growth can also be driven through the value chain, with increased domestic feed production and processing.

Aquaculture reviving many coastal economies, says report

The social impact of fish farming in Iceland can be diverse, according to the official body Statistics Iceland.

It says aquaculture has increased the number of sources of foreign exchange for the national economy, and has accounted for over 5% of the value of all merchandise exports.

This development is extremely positive, as strong and diverse exports are a fundamental pre-requisite for improved living standards in this country.

The figures from Statistics Iceland show that aquaculture has a major economic impact on the people of the various regions and that has not been lost on those who live there.

Some of these areas went into decline after the loss of deep sea fishing some years ago, but now thanks to aquaculture, the economy has become more dynamic and diverse, while the population has increased and this has revived the housing market.

The increased activity of aquaculture companies is clearly visible in labour market figures, where employment income has never been higher.

The Statistics Iceland figures show that the number of people employed in aquaculture has almost quadrupled in the period 2010-2022, while employment income, at 2022 prices, has increased more than six-fold, to ISK 3.4 billion.

KPMG Analysis says these figures do not include indirect jobs, adding that the economic impact of aquaculture is extensive. The conclusion of KPMG’s analysis for Iceland is that for every job in aquaculture, almost the same number of indirect jobs are created.

Experience shows that aquaculture has strengthened other industries directly and indirectly, for example, through increased utilisation of accommodation space, increased activities of contractors and transport companies, and more diverse jobs.

Reykjavik urged to help revive mussel farming

There are great opportunities for the revival of Iceland’s mussel farming, according to a consultation group working on the restoration of this modest, but important, sector.

That is if the government can show enough support, they stress.

Mussel farming was once a small but relatively important part of the aquaculture scene. However, its slow decline began a decade ago, with companies dropping out of the business year on year.

Some blame that decline on the Althingi, Iceland’s parliament, passing a law on shellfish farming a few years ago.

The law was seen as controversial, and the heavy regulation had a devastating effect. A decade later, no mussels were farmed in Iceland and mussels disappeared from the market.

The group believes mussel farming could create many jobs in fishing communities around the country, but the state would have to assist and take care of the analysis of algae toxins in the product while the industry is being developed.

ICELAND FACTS

- Population: 390,000 (approx.).

- Iceland gained full independence from Denmark at the end of the Second World War.

- More than 60% of Icelanders live in the capital Reykjavik.

- Vikings discovered Iceland by accident 1,100 years ago, making it one of the last places on Earth to be settled by humans. The language is linked to the Vikings.

- Area: 103,000 square kilometres or 39,769 square miles.

- Fish and fishery products are the country’s main source of export income followed by aluminium products.

- Iceland experiences some 26,000 earthquakes a year, the majority are very small, but every now and then a large and, occasionally terrifying, eruption occurs.

Why not try these links to see what our Fish Farmer AI can tell you.

(Please note this is an experimental service)