Algal blooms: a growing threat

While algae are part of the marine ecosystem, certain species can create dangerous conditions for farmed fish or produce toxins making shellfish unsafe for consumption. Fish Farmer’s Algal Blooms webinar on 4 June, in association with Poseidon Ocean Systems, featured a panel discussing the causes of harmful algal blooms (HABs), how to improve the prediction of HABs and mitigation actions.

Our panel for the webinar was made up of:

- Linda Lawton, Robert Gordon University

- Jill Couto-Phoenix, Lantra

- Beth Osborne, Loch Duart

- Sarah Riddle, SAIC

- Robert Wyvill, Poseidon Ocean Systems

- Robert Outram, Fish Farmer magazine (Facilitator)

Sarah Riddle of the Sustainable Aquaculture Innovation Centre (SAIC) said: “We were always aware harmful algal blooms could be a challenge in certain months of the year, I would say April to end of September.

“We find ourselves now not being able to say with confidence that we will only have a threat of harmful algal blooms within certain months. We are seeing that season changing quite dramatically.”

Robert Wyvill introduced Poseidon’s suite of aquaculture technology and stressed: “Our focus is to improve fish welfare.”

The company has developed the Flowpressor compressor system, an aeration system designed for aquaculture; the Oxypressor for oxygenation, to be used in conjunction with the Flowpressor; and the Depth Charge Plume, for oxygen diffusion. Poseidon also produces the Trident pen.

As Wyvill explained: “Poseidon provides systems and solutions which provide climate resilience to the farmer against many challenges, all derived from warming and changing oceans, including low oxygen, warmer water, jellyfish, sea lice and harmful algae.

“Poseidon’s life support systems, with the Flowpressor and Oxypressor, can have a very positive effect against harmful algal blooms, especially when used in conjunction with a robust harmful algae monitoring programme.”

For each system sold, he added, Poseidon provides some hours of training in harmful algae monitoring programmes, as well as in the use of the Oxypressor and the Flowpressor, based on more than 20 years’ experience gained in British Columbia.

He said: “The goal is to ensure that every farmer has a robust life support system, knows how to use it and is fully trained in harmful algae monitoring programmes.”

‘Climate extremes are occurring more regularly’

Loch Duart’s Beth Osborne said: “We produce 6,000 to 10,000 tonnes of salmon per year in 12 sites across three separate geographic areas. Each site has their own distinct environment.

“As Health and Welfare Manager, I’m responsible for keeping health and welfare at a high standard for all of the salmon in our care, which currently is sitting at almost 4.7 million individuals.”

She added: “Environmental monitoring and training for all sea site staff to recognise any change in the environmental issues that can lead to stress is a huge part of my role.”

Potentially algal blooms are a huge issue for Loch Duart.

Osborne said: “A HAB has the ability to come in and wipe a site out in less than 24 hours, without much warning.

“Climate extremes are occurring more regularly, and many species can adapt to this changing environment very easily, such as jellyfish. They take advantage of niches that are being cleared from other species during rapid climate change, and they are generally considered a climate winner.

“Most species of jellyfish, macro and micro, can have a huge impact on the health and welfare of the salmon. So, HAB and jellyfish monitoring, identification, and the speed of reaction from the farmers is very key to ensuring survival and maintenance of welfare during the high-risk season, which, as Sarah said, is changing.”

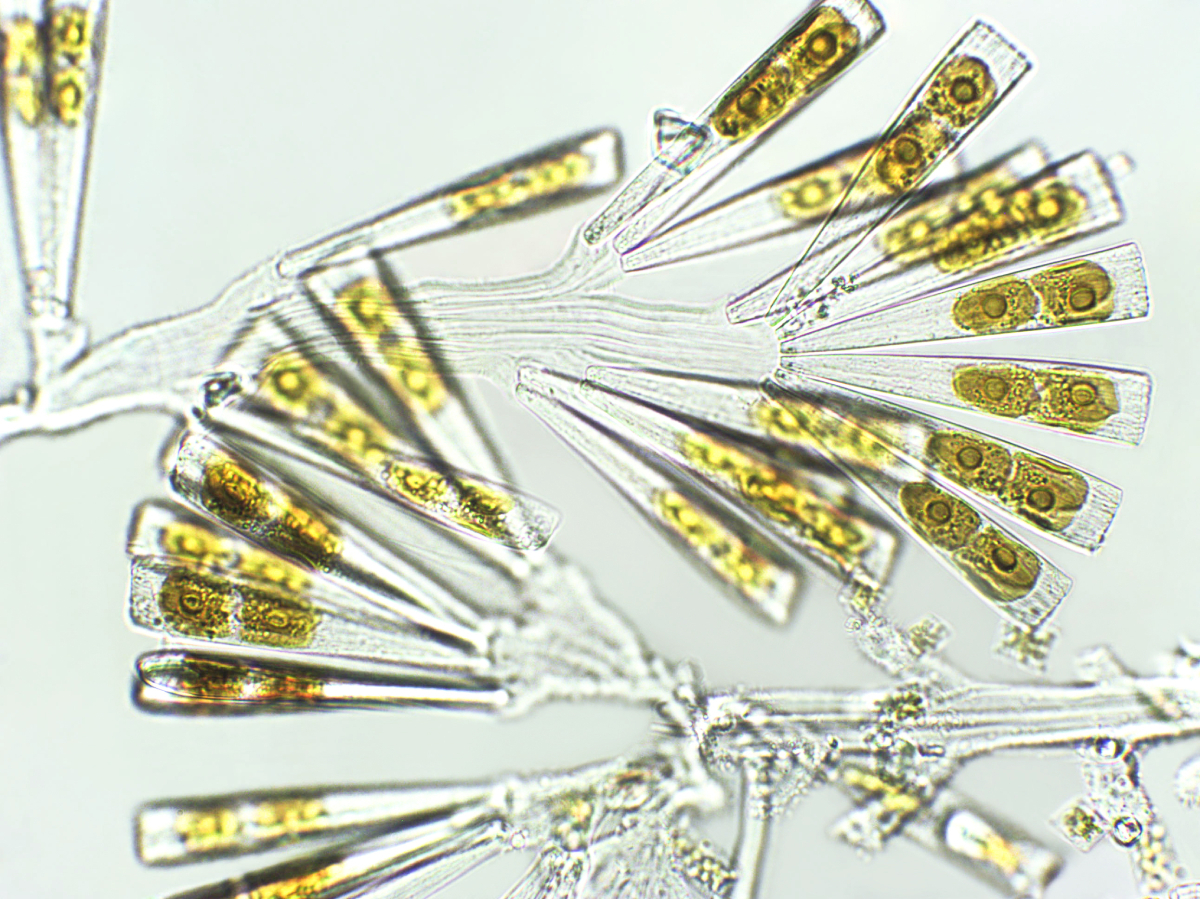

Professor Linda Lawton’s research focuses on cyanobacteria in freshwater and seawater. This includes growing them and isolating the toxins – RGU is the world’s biggest producer of purified cyanobacteria toxins for research – as well as finding ways to detect and destroy them.

She said: “We’ve spent many, many years developing detection methods, and more recently with my colleague, Professor Christine Edwards, we’ve been looking at the lateral flow tests, which is a very important gap in the market.”

Techniques for eliminating these organisms are also being developed. RGU is exploring photocatalysis, with catalysts activated by light that can destroy both the microorganisms and the toxins they create, as an alternative to existing chemical treatments. Some catalysts produce hydroxyl and superoxide radicals, which are lethal to the HABs but very short-lived.

Others are based on carbon nitrides, organic compounds derived from carbon and nitrogen.

The catalysts can be activated by barely visible near-ultraviolet light from LEDs, and some plankton species are even attracted by light, which can make it possible to trap and destroy them.

Jill Couto-Phoenix is Head of Aquaculture with Lantra, the leading body for environmental and land-based skills training in the UK.

She said: “We all know that the aquaculture sector is growing and adapting very quickly. There’s a lot of R&D and a lot of innovation, which, of course, means our collective thinking and knowledge of the area is also moving rapidly, and this translates into a plethora of different skills.

“So, our role is to work with many different partners, including academia and specialist industries, to try and bring this fresh knowledge and then deliver it straight to the learner, so that, over time, this new information gets put into practice.”

As Couto-Phoenix explained, with increasing knowledge regarding HABs, it was recognised that there is a need for agile, easy-to-access training that would be practical and benefit farmers. Lantra is therefore delivering a course, in short modules, for anyone who needs to know how to sample and identify harmful algal species.

She added: “This then helps farmers understand what is in the water, so that they can adapt and act accordingly.”

A serious threat

How do HABs rank as a threat to farmed fish? Robert Wyvill said: “I think it ranks as high as the likes of AGD [amoebic gill disease] and PD [pancreatic disease], and it’s definitely getting worse as water temperatures rise.”

Sarah Riddle said that SAIC had been involved in several projects to identify which algal species constitute a threat, as well as ways farm staff can identify them, and whether better means of forecasting HABs could be developed.

She added: “It’s not just what’s in the water, but linking that threat to the fish, and then looking at mitigations.”

As Beth Osborne explained, algal blooms and jellyfish swarms can affect fish health in various ways: some species have sharp spikes which can damage gills, while the biggest threat is oxygen depletion. Jellyfish can also lead to secondary infections.

She added: “This is only getting harder, and it’s very, very important to be monitoring 24 hours. Taking one sample a day is not enough, you can easily miss things.”

There is a consensus that, as the Atlantic Ocean gets warmer, algal blooms are becoming even more of a problem.

As Beth Osborne pointed out: “If you think about the amount of available energy in an environmental system, a change of 1.2 degrees in the Atlantic Ocean equals a huge amount of potential energy.”

This can fuel the growth of certain species and make large algal blooms more likely.

Another question concerned whether the topography and conditions of some loch systems make them more vulnerable.

Robert Wyvill commented: “I was in a farm where we had a red tide come in, and because of the way that the loch system was, it was stuck in for quite a number of days.

“So it’s about having a stringent harmful algal monitoring programme on your site, so that over a period of time, you can start to map out when you’re most likely to have these events happening, and then using a life support system.”

Beth Osborne said: “There are definitely certain sites [at higher risk], such as long, narrow, and deep loch sites that get shallow further inland.”

Historic information, tide tables and wind direction all need to be taken into account, she added: “Plankton sometimes get trapped when the tide’s not great enough to provide a complete exchange of water.”

Mitigation strategies

What can and should farmers do when faced with a HAB?

As Beth Osborne explained, there are three types of harmful effects that can be experienced with a HAB: physical, toxic and oxygen depletion.

Plankton photosynthesises during the day, so overnight you can have a dip in oxygen, and unfortunately most plankton is more tolerant of low oxygen than salmon are.

Farmers therefore need to be able to supply supplementary oxygen, but preparing for this can take time, if for example heavy equipment has to be towed to the site. This means that anticipating the problem is crucial.

Suspending feeding temporarily is another mitigation tactic, as Osborne explained. A fish with a bellyful of food has twice the metabolic rate overnight as one with an empty stomach, meaning that it requires more oxygen. Of course, prolonged starvation can bring its own issues.

The timing of feeding can also help, for example one large feed at 1pm might allow the fish to digest the food by nightfall when the oxygen level drops.

Aeration and the use of tarpaulins to protect the fish can help, as can moving the fish to a water level where there are fewer algae, but all of these solutions entail understanding the nature of the algal species and the health status of the fish.

Understanding the species you are dealing with is very important, Robert Wyvill stressed. For example Heterosigma – associated with red tides – requires aeration combined with skirts for the pens, while some other species are best dealt with through aeration but no skirts.

Oxygenation and withholding food are, as Beth Osborne also said, potential strategies. But Wyvill stressed: “This, of course, comes back to the harmful algae monitoring plans and making sure that your team are as trained as possible in algae identification.”

Prediction is also critical. As Sarah Riddle set out, work is underway on a collaborative basis, with the Scottish Association for Marine Science in Oban leading the way, supported by SAIC and other organisations, to develop a monitoring and forecasting system for HABs. This project began with toxin monitoring for shellfish farmers, and it is hoped that it could become a dynamic, rolling forecast for fish farmers.

Technology such as the Flow Cytobot currently deployed off Shetland, could help to build up a complete picture of the risk from HABs.

As Beth Osborne explained, however, the most basic early warning system is neighbouring fish farms keeping each other informed of the situation, day-to-day.

She said: “It’s about having good relationships with other local farms. We are regularly in contact, saying, oh, we’re seeing this, have you seen this? It could be coming your way, please keep an eye out.”

As she pointed out, there is actually a great deal of data being collected in the ocean, but we need to get better at collaborating, sharing that data to build up a complete picture.

She added, though: “I do appreciate that it’s a very messy environment for prediction. Our weather in the UK is hard enough to predict, two days in advance, and that’s pretty much all you can actually do reliably.”

Linda Lawton agreed: “Joining up all the data that we’ve got, and working together on this, will be hugely beneficial.”

She added that Robert Gordon University is refining systems for the faster identification of algae, both marine and freshwater.

Recent studies have suggested that salmon farms do not contribute significantly to the nutrients in the sea that can encourage HABs, but in the long term, as Sarah Riddle explained, multi-trophic aquaculture – where finfish farming is combined with farming shellfish or seaweed, for example – could help to absorb nutrients and also contribute to preserving biodiversity in the marine environment. This would help to reduce the risk that one algal species could grow disproportionately.

Learning from international experience will also be important. Poseidon’s technology was developed in British Columbia, Canada, where algal blooms had been a major problem.

Robert Wyvill said: “There were mass fish mortalities all over British Columbia. Now they have a harmful algae monitoring plan and they’re able to map out when events are likely to happen, and they have effective life support systems in place.

“So I think we could definitely learn a lot from Canada, and also from Chile.”

Where do we go from here?

What’s next? Jillian Couto-Phoenix said: “I’d like to be able to arm every single farmer, regardless of where they are, with skills and training, so that they can then feel confident in the data that they’re looking at, and what they’re recording.”

Beth Osborne said: “I’d like to see open communication and collaboration, but not just between the industry, but between everybody who’s operating in the marine environment. By the time a fish farmer is actually taking a sample and identifying it, it’s already on your farm, it’s already almost too late.”

“I would like to get out of the lab and into the fish farm with some of our technology,” said Linda Lawton. She added: “That is a huge jump. We’re making baby steps just now, so if we could make baby steps with some of the excellent people out there [in the sector], it’d be lovely.”

Sarah Riddle was optimistic: “There is massive proactivity within this sector and there’s been a huge onboarding of technology. We never rest, but we want to be smart, we want to be efficient.

“It’s not an easy nut to crack, but there is such commitment here.”

Robert Wyvill concluded: “Every company should have a robust harmful algae monitoring programme in place, and a life support system.”

You can see the whole webinar online at www.fishfarmermagazine.com/news/aqua-agenda-webinar-video-harmful-algal-blooms

The next Aqua Agenda webinar is on Feed & Feed Strategies, in association with our partner Tidal, and it takes place on 10 September 2025. For details see www.fishfarmermagazine.com/events-webinars/feed--feed-strategies

MORE QUESTIONS ANSWERED

The audience came up with some great questions during the webinar and we did not have time to deal with all of them on the day. Here are some questions (and answers) by way of a follow-up.

Q: Are there any negative aspects to the use of photocatalysts eg effects on salmon or non-target marine species?

A: The process shouldn’t affect salmon but will be monitored, the main concern would be other microbiota.

Q: Is the photocatalyst technology already available at an industrial level?

A: No, RGU are still looking for collaborators in the industry.

Q: Is it imperative to take sampling points at various locations and depths around the farm, and how often per day would be adequate?

A: Continuous monitoring systems would be the most effective, drawing water from multiple depths and locations.

Q: Are farmers using the HAB reports established by SAMS?

A: Yes, the reports from SAMS are available at www.habreports.org and fish farmers do make use of them.

Q: Not a mention of bubble curtains? There are many successful cases in Canada and Chile.

A: Bubble curtains are also a potentially useful defence against HABs and jellyfish swarms, and Mowi, to name one operator, is trialling them at some of its Scottish sites.

Why not try these links to see what our Fish Farmer AI can tell you.

(Please note this is an experimental service)